The phonograph collecting community lost one of its most talented members when

William C. Ptacek was tragically killed in a boating accident on July 3, 2004, at

the far-too-young age of 46. Quiet and soft-spoken in demeanor, Bill was unfailingly

generous and warm-hearted and was well-liked and respected by all who had the pleasure

of meeting him. Bill was modest about his own collection and very few people knew

how many rare and highly coveted phonographs he had. Bill's particular passion, like

my own, was for tinfoil phonographs. However his interest lay not in collecting the

machines, but rather studying them and making the world's most precise replicas for

other collectors to enjoy.

Bill Ptacek imitating the classic pose of Thomas Edison originally taken

at Matthew Brady's studio in 1878. The phonograph is Bill's own reproduction.

Bill was a master machinist who owned and operated a very successful machine

shop, Ptacek Machine Works (also known as Kustom Machine), in his home town of Oakes,

North Dakota. With his uncommon knowledge, experience, attention to detail, and access

to the finest precision equipment, Bill was uniquely qualified to produce replicas

of incomparable quality.

The first tinfoil phonograph to capture Bill's attention

was the famous "Kruesi" machine -- the very first prototype phonograph

made in December 1877 by Edison's assistant John Kruesi. As the first phonograph

ever made, this is an obvious choice for many talented machinists who wish to try

their hand at building a tinfoil replica. Thanks to Thomas Edison, this is also the

easiest phonograph to reproduce: in 1929 Edison had his staff draw up blueprints

of the machine in order to make replicas for museums who requested examples. These

blueprints have long been available to the public through the Edison National Historic

Site. However, detailed as they are, the old blueprints are incomplete and do not

specify a few small but important details, notably in the design of the stylus. Any

good machinist can work around this problem by using his own ingenuity, but Bill

recognized that the only way to make an exact replica would be to inspect

and measure the original and fill in the missing blanks of the old blueprints. Consequently

he flew to New Jersey to examine Kruesi's handiwork directly. He carefully copied

every single detail of the original phonograph, right down to extraneous machining

marks and other unintended original imperfections. Over the next several years Bill

made about 35-45 of these exquisite replicas.

Bill Ptacek (right) at the Edison National Historic site, examining the

original prototype phonograph with vintage recording expert Peter Dilg.

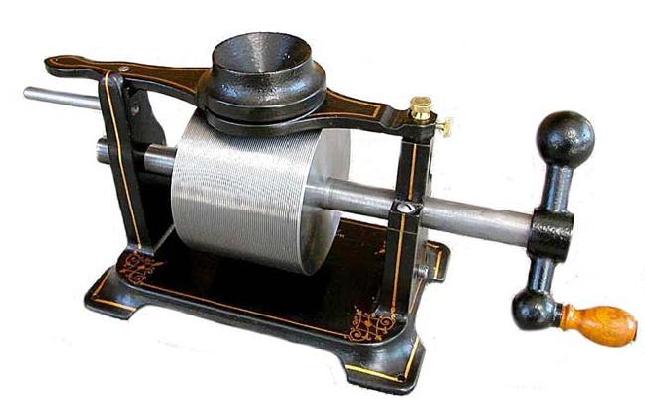

Replica "Kreusi" tinfoil made by Bill Ptacek in 1996.

Bill next turned his attention to a far more challenging machine: the huge

and impressive Bergmann Exhibition tinfoil phonograph of late 1878. This machine

was Bill's special passion -- in fact, he was the only person in the world who has

ever personally seen and studied every single surviving example (twelve in all, including

prototypes), a quest which took him from Los Angeles to Washington, New Jersey to

Glasgow, Dearborn to Munich. No one knew more about these machines than Bill Ptacek.

In 1996 he persuaded curators at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington to not

only grant him access to Bergmann serial #154, which had been donated to the museum

by Edison himself in 1916, but also to completely disassemble the machine in order

to make precise drawings of every dimension. With hundreds of close-up photographs

and reams of drawings and measurements Bill was able to make replicas which were

faithful to the original down to the smallest detail. So perfect were these reproduction

Bergmanns that the Edison National Historic Site bought one of the very first to

use for public demonstrations, even though they have many original tinfoil phonographs

in their collection. The Thomas A. Edison Memorial Tower and Menlo Park Museum

in Edison, NJ, also purchased one of these perfect replicas. Bill produced a total

of 12 in a limited edition, all of which were pre-sold even before completion.

Replica Bergmann Exhibition tinfoil phonograph by Bill Ptacek. This particular

machine is now in the collection of the Thomas A. Edison Memorial Tower and Menlo

Park Museum in Edison, NJ.

In 2000, when I was researching my book Tinfoil

Phonographs, Bill and I travelled together to museums and collections all

around the United States as well as in Paris to study original tinfoil machines.

During our visit to the Smithsonian the curator once again gave us unlimited access

to every tinfoil phonograph in their archives. While I photographed and examined

machines for my book, Bill set to work disassembling and measuring three of the Smithsonian's

Edison Parlor Model tinfoils, including one which had been donated by Alexander Graham

Bell.

In the archives of the Smithsonian, Bill disassembled and made engineering

drawings from the museum's collection of Edison Parlor Model tinfoil phonographs.

While we were at the Smithsonian I found a very obscure reference in an old

file folder mentioning an all-brass Bergmann Exhibition tinfoil that reportedly existed

in a museum in Glasgow, Scotland. This was an eye-opening revelation -- all reports,

even in the extremely heavily researched "Edison Papers Project" books,

claimed that none of these hand-made machines were known to exist. With the help

of a friend in England, who had been born and raised in Glasgow, the museum was finally

located and the appropriate curator contacted. This was a surprisingly difficult

process since the name of the museum had changed since the Smithsonian's note was

filed, and most of the Glasgow museum's staff were unaware of the phonograph's existence

(the machine had been in storage since 1944 and has never been publicly displayed).

A curator, Alastair Smith, finally tracked it down in a museum storeroom and took

photographs, which were subsequently emailed to me. When I saw the pictures I felt

as though I had just found the holy grail -- this was indeed a previously unknown

example of Edison's top of the line tinfoil phonograph, the finest and most deluxe

ever produced. I immediately emailed the pictures to Bill. Less than three weeks

later, on Thanksgiving Day, 2000, Bill Ptacek flew to Scotland with the single goal

of seeing the machine in person. Once again, he so impressed the curators with his

knowledge and dedication that he was allowed to disassemble this priceless one-of-a-kind

phonograph. I immediately commissioned Bill to make a reproduction for my own collection.

Price was never even discussed -- I knew that he would spare no effort in his quest

for perfection and it would be well worth whatever it cost to make. In January, 2002,

he delivered the finished replica to my house and today it is one of my most cherished

treasures.

Disassembling the unique original brass Bergmann Exhibition tinfoil phonograph

in Glasgow on Thanksgiving Day, 2000.

A more exquisite reproduction tinfoil does not -- could not -- exist. Tinfoil

phonographs, by their very nature, require extreme precision in their manufacture.

Tolerances are critical and even the slightest deviation from perfect alignments

will prevent the machine from functioning properly. This made the original machinist's

job very difficult, but Bill's job was infinitely harder. While the original maker

needed to be precise on critical points, he had considerable flexibility on other

details. For example, if a flywheel was a few thousandths of an inch wider or narrower

than the blueprints it had no affect on performance. But to make an exact replica

there can be absolutely no deviation from the blueprints. Bill was obliged to respect

every single detail, every single dimension, down to a thousandth of an inch or less,

however insignificant that particular point might seem. With a machine as large (over

three feet wide) and heavy (over 125 pounds) as the brass Bergmann "Drawing

Room Instrument" tinfoil, the number of individual pieces and critical dimensions

is almost unimaginable. Over 400 hours of highly skilled labor went into the production

of this machine. The result is a monumental testament to Bill's incomparable skills

as a machinist and expertise as a tinfoil historian. It is truly a masterpiece. (In

the following year two other collectors commissioned Bill to make replica brass Bergmanns

for their own collections.)

At the same time as he was working on the first brass Bergmann, Bill was also

preparing another limited edition series, this time of the famous "Brady"

tinfoil phonograph. The Brady, so-called because Edison was photographed with this

machine in the studios of Matthew Brady in Washington in April 1878, is perhaps the

most famous tinfoil phonograph of all, simply because the picture has been reproduced

thousands of times over the past century and a quarter. Despite its legendary fame

no one had ever attempted to make an accurate replica of the Brady tinfoil. Only

two originals have survived, one at the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan and the other

at the Edison National Historic Site in New Jersey. Bill and I visited both places

several times, and he subsequently set about making 14 replicas which are exactly

like the originals in every detail. They were delivered to their appreciative new

owners in 2002.

With blueprints for the Brady still in hand, Bill had an inspiration.

Why not make a "baby" Brady? Simply reduce the blueprints down to one-third original

dimensions to make an exact scale model. It was an ingenious idea, but it proved

to be anything but simple in the end. The problem was that Bill refused to do any

work that was not absolutely perfect. He would not cut corners to simplify the process,

even if the result would never be noticed by anyone. This meant that for the miniature

Brady tinfoil he could not use "off the shelf" hardware. Everything had

to be precisely 1/3 original scale and exactly the same as the full-sized

original. Every single piece must be hand-made and/or hand-finished. To his dismay,

he discovered that making and assembling the miniature baby Brady tinfoils took just

as long as making the full-sized replicas. In fact, it took even longer because of

the finer tolerances. However there was no way he could sell the miniature, which

was considered a novelty, for anywhere near as much as the functional full-sized

version. Making tinfoil replicas was never particularly profitable for Bill -- it

was primarily a labor of love for which he received only a few dollars an hour for

his labor -- but the baby Brady proved to be a hopeless money-loser. He cast enough

bases to produce twenty miniatures, but with so many other projects taking priority

he only completed nine.

Full-size and one-third scale model versions of the "Brady" tinfoil

phonograph made by Bill Ptacek.

Bill's last tinfoil project was the top-mount Parlor Model tinfoil. Once again,

his extreme attention to detail was reflected in the exquisite precision of the completed

pieces. Even the original shipping box, with its stencilled label on the sides, was

copied precisely. Bill intended to produce a limited edition of 12 Parlor Models,

but unfortunately he only completed five before his untimely demise.

After a year of very intensive work expanding his machine shop to keep up with

his rapidly growing day-to-day business, Bill was looking forward to completing the

last of the Parlor Model replicas so he could move on to his next project, which

would have been his crowning achievement. He planned to make 12 replicas of the "miniature

Class M," a 50% scale model of an 1888 Class M Electric phonograph. Edison had

made a single example of this exquisitely detailed little machine for exhibition

at the World's Fair in Paris in 1889. The original phonograph is in the collection

of the Edison National Historic Site but has not been publicly displayed. Bill spent

many, many long hours making blueprints of this extraordinary machine. The amount

of detail involved is almost beyond imagining, but Bill was undaunted and was prepared

to make a working copy that would be absolutely precise. Unfortunately he only completed

a very few patterns of the many needed castings before he died. Sadly, this ambitious

project will never come to pass.

Bill Ptacek with Edison's original "miniature" Class M at the

Edison National Historic Site in 2002.

Bill recognized that the extremely high quality of his reproductions could

potentially lead to their being confused with originals in the future, as they gain

natural patina with age. To protect future collectors he was always careful to mark

all of his replicas with his initials or name, along with a serial number.

Bill's

skills were not limited to making complete reproductions. He also made impossible-to-find

parts for many rare machines in collections and museums around the world, helping

to restore otherwise unrestorable phonographs. His work was regarded with admiration

by all who saw it.

Bill Ptacek was obviously very passionate about phonographs,

but the hobby did not consume his life by any means. Bill was a private pilot, hot-air

balloonist, motorcyclist and sailor. He was an expert on steam engines as well as

Stirling hot air motors, and Model T and Model A Fords. He was an avid traveller

who visited Europe at least once or twice a year and travelled all over the United

States in his unending quest for knowledge about people, places, and things. He was

passionate about wine and loved to visit the nearby vineyards on his trips to my

northern California home. Annual trips to Paris for the Beaujolais Nouveau festival

in November had become a new tradition. He was truly a Renaissance man, someone with

unlimited interests, phenomenal talent, and a big heart. Generous and kind to a fault,

he was a man of rare good humor, insight, and skill. He was my best friend and I

will miss him.

Rest in peace, Bill. God bless you.

(A memorial fund

to support students in mechanical engineering has been established. Contributions

may be made to the William C. Ptacek Scholarship Fund, c/o First State Bank of LaMoure,

P.O. Box 49, Oakes, ND 58474.)